by Tomiwa Ilori

Communications surveillance has become more insidious. African governments continue to invest in intrusive surveillance equipment that not only violates human rights, but also contributes to closing the civic space. This essay argues that in correcting policy on communications surveillance especially in Africa, stakeholders must turn to rights-respecting laws with directions from within the African context in this regard.

The terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre on 11 September 2001, won’t be forgotten in a hurry. It set off repercussions that were not immediately obvious even two decades after – the trade-off between human rights and public security. In particular, it renewed the conversations on policy setting for communications surveillance across the world.

More than a decade later, Edward Snowden – a former subcontractor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) revealed that the National Security Agency (NSA), together with telecommunication companies, spies on US citizens and other countries’ leaders and people through various intrusive surveillance technologies on grounds of national security.

Privacy International defines communications surveillance as the “monitoring, interception, collection, preservation and retention of information that has been communicated, relayed or generated over communications networks to a group of recipients by a third party.”

Today, more governments are emboldened in their deployment of indiscriminate communications surveillance, arguing that such are fine, in so far as they guarantee public safety.

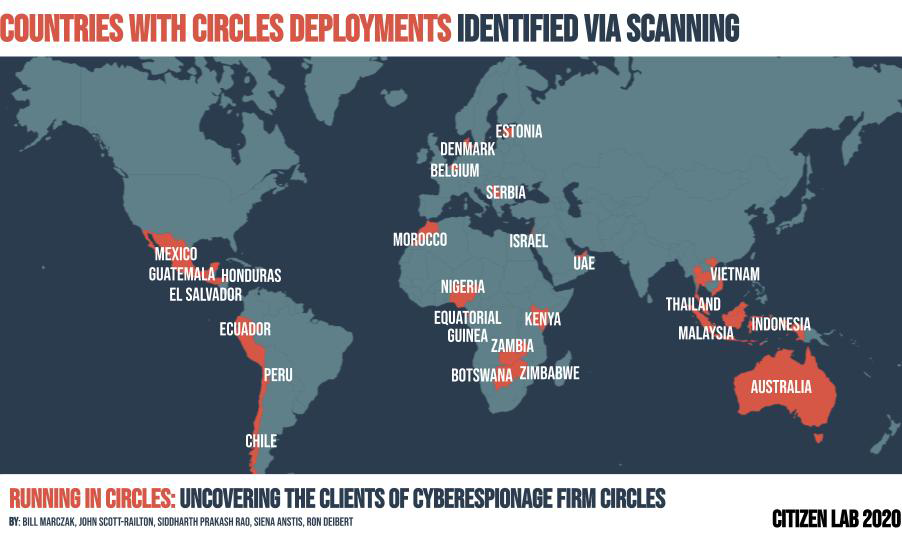

In 2021, Citizen Lab released a report on 25 countries conducting cyber-espionage across the world. Seven of those are African countries which include Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Equatorial Guinea, Morocco, Botswana, Kenya and Zambia, and they feature prominently in the report as having ties with an Israeli telecoms company called Circles.

The report by Citizen Lab points to three alarming facts on communication surveillance:

- spyware deployment is carried out by governments, especially those with troubling records of human rights abuses,

- intrusive technologies have become more insidious; and

- telecommunications companies are complicit in indiscriminate deployment of communications surveillance.

These confirm that governments, together with telecommunication companies do not engage in surveillance only to ensure public safety, but also use these new technologies to track government opposition, journalists and human rights defenders. What this does is throw up the policy gaps on communications surveillance in most systems, including those in African countries.

So knowing this, what can those who are not part of that government decision do?

First we have to understand that the primary standard of international human rights law, is explicit on how surveillance technologies can be deployed.

The major principles under international law as they have been discussed by experts include legality, legitimate aim, necessity, judicial oversight and due process, among others

While these principles seek to protect the right to privacy, they also acknowledge the need for surveillance in public interest but with the necessary checks and balances in place.

In many African countries, these principles are not complied with. This is because where there are laws on communications surveillance they are mostly inadequate.

African countries which carry out surveillance do not usually have the requisite law in place and where they do, these are either inadequate or abused or both.

This has posed serious challenges with respect to the right to privacy and the increasing need to conduct legally permissible surveillance.

In Nigeria, not only is the legal regime on interception governed by a secondary law, but the manner in which they are carried out are opaque and unaccountable. Likewise, in Uganda, both the Regulation of Interception of Communications (RICA) and the Anti-Terrorism Act which touch on communications surveillance, do not have clear oversight mechanisms.

In a case decided on 4 February 2021, the South African Constitutional Court ruled that the mass surveillance by the South African Communications Centre was unlawful and invalid. It called for the review of the Regulation of Interception of Communications (RICA) to be brought in line with the country’s constitution.

Despite the Constitutional Court judgment, and its possibility for positive reforms in the surveillance sector in South Africa, one journalist had her house broken into and laptops stolen, another was said to be under surveillance after investigating corruption allegations within the Crime Intelligence (CI) division of the South African Police

Beyond terror attacks, the COVID-19 pandemic has renewed tensions between the right to privacy and public health in many countries. While there is the need to protect against the pandemic there is also the need to protect the right to privacy. It is obvious that the right to privacy should not be sacrificed on the altar of the right to public health and vice versa.

The question is how communications surveillance, given its insidious nature, can be regulated. Combining the political power of states with the economic power of the communications surveillance sector already put at US$12 billion, regulation seems far-fetched. With this powerful dynamic, human rights are being sacrificed to accommodate the whims of powerful actors. But there is hope, the type however, that requires more work.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the African Commission) recently revised the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa, which provides specifically against indiscriminate use of communication surveillance. Principle 41 provides for policy solutions which require member states not to engage in indiscriminate communications surveillance except provided for by law and in compliance with international human rights law principles.

Individuals and organisations who work in the social justice sector are not left without the power to push back. This, among others, can serve as a basis for asking the difficult questions from governments and demanding answers.

One of the major principles of ensuring rights-respecting communications surveillance practice is legality. Most African countries do not have specific laws on communications surveillance. Where these exist, they are secondary laws that do not allow for enough direct public participation through a primary law enacted by parliaments. There is a need for laws which must be in compliance with international human rights law and the provisions of the Declaration.

Civil society actors should continue working hard to open up the surveillance sector. One way to do this is to approach the courts for judicial review, as in the case of South Africa

Communications surveillance is not mutually exclusive of human rights protection. The strong narrative woven by governments that in protecting public safety, surveillance needs to be conducted without oversight is a recipe for disaster. These policies can be designed in such a way that they respect privacy and protect human rights by paying attention to suggestions described above.

In resolving the major tension that often arises in the use of communications surveillance, major stakeholders like governments, private sector and civil society must work together to design effective policy solutions to communications.

This will assist in no small measure in placing intrusive technologies under the purview of rights-respecting laws while deploying these technologies to more lawful uses.

Tomiwa Ilori is a doctoral researcher at the Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria. He also works as a researcher at the Expression, Information and Digital Rights Unit at the Centre. He can be found on Twitter at @tomiwa_ilori.